Working with Grids¶

Now that we’ve got vectors explained, we’ll go over different ways of creating grids, and some different use-cases for grids.

Grids by Vectors¶

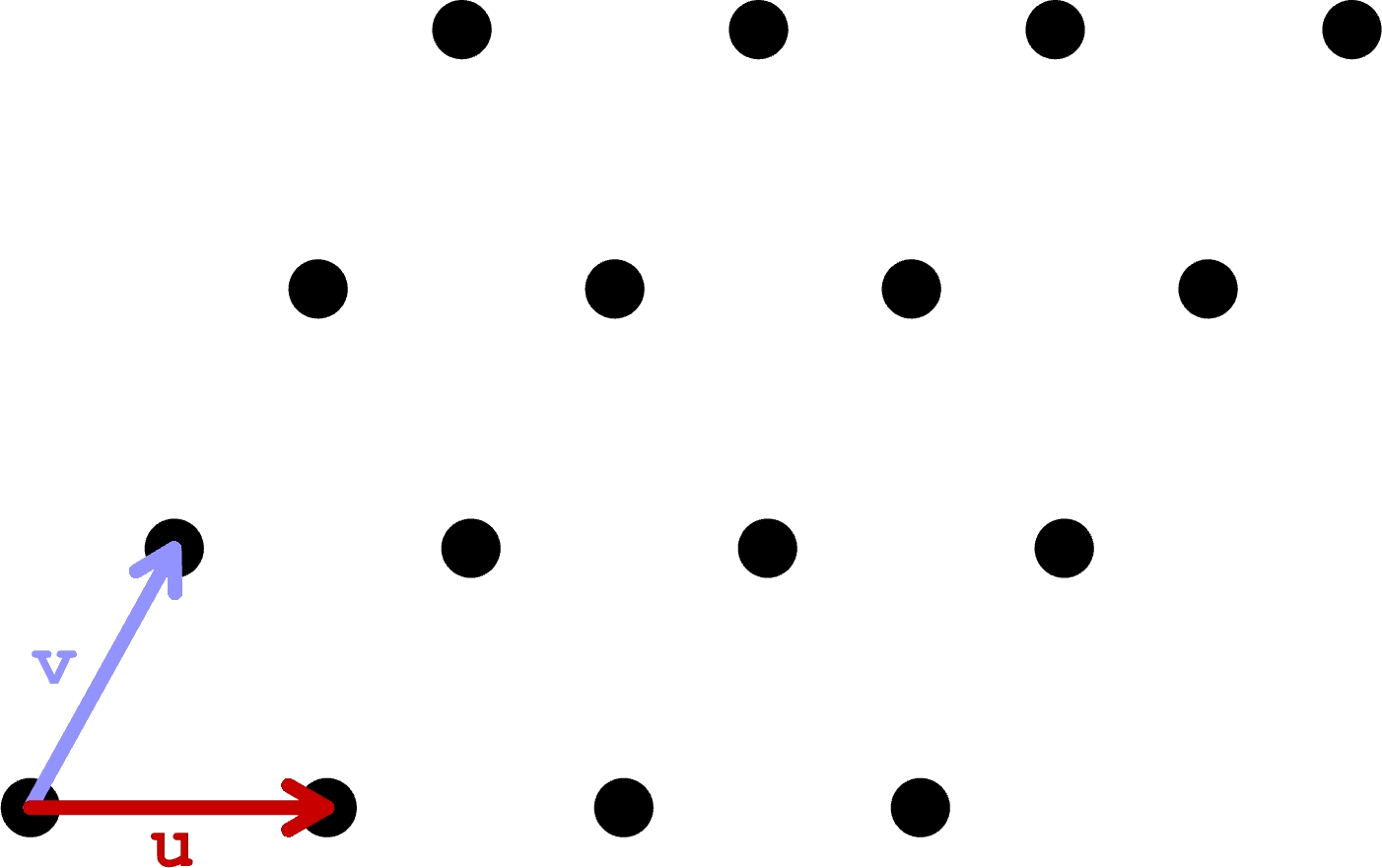

Generally, we’ll be starting with 2-dimensional grids. While these are in \(\mathbb{R}^3\)

and made with Vector3d, we only need two basis vectors (\(\mathbf{u}\)

and \(\mathbf{v}\)) to create every point in the grid. We can just set the z

component of these vectors to 0.

Furthermore, it’s often useful to use the integers (\(\mathbb{Q}\)) as your field

when building grids from vectors. This lets you use integers for \(a\) and \(b\) in

\(\mathbf{w} = \begin{bmatrix}a & b & 0\end{bmatrix} = a\mathbf{u} + b\mathbf{v}\).

If you then store grid points in a data tree or list of lists, the grid point at

grid[a][b] is simply \(a\mathbf{u} + b\mathbf{v}\).

Choosing a different basis can let you create interesting grids. For example, the hexagonal and triangular grid components in Grasshopper create grid points using basis vectors that are \(30\deg\) apart. The center points of hexagons in a hexagonal grid are equivalent to the corners of triangles in a triangles in a triangular grid, and vice versa. Square grids can be made with the standard basis of \(\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}\) and \(\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\) or with \(\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}\) and \(\begin{bmatrix}1 & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\), the latter of which is indexed diagonally.

Note

The grid used in Assignment 2: 2D Cubies Illusion is actually made with 3 basis vectors instead of 2, even though its a 2D grid. This is because the grid is a projection of a cube onto the XY plane. Using 3 basis vectors means each point in the grid can be made with an infinite number of combinations of the basis vectors, but given the nature of the problem, this is totally acceptable.

The basis vectors used are:

and each correspond to the projected version of the corresponding basis of the

cube we’re projecting onto the XY plane. get_point(u, v, w) just computes

\(u\mathbf{u} + v\mathbf{v} + w\mathbf{w}\).